Reading - The Drunken Boat

One Hundred and Fifty Years at SeaArthur Rimbaud, the enfant terrible of French poetry, was born in 1854 in the town of Charleville, which lies on the banks of the Meuse in the Ardennes, a few miles short of the Belgian border.

The Strange Tale of The Drunken Boat

Le Bateau Ivre (The Drunken Boat) is one of Rimbaud’s best-known poems. It was written in the summer of 1871, when Rimbaud was sixteen years of age, and made its inauspicious debut when the young poet recited it to one of his school friends, Ernest Delahaye, on the eve of his move from Charleville to Paris. The simultaneous departure, of the Boat in the poem and Rimbaud in real-life, is the first of the many strange alignments between the destiny of the poet and voyage of his drunken boat.

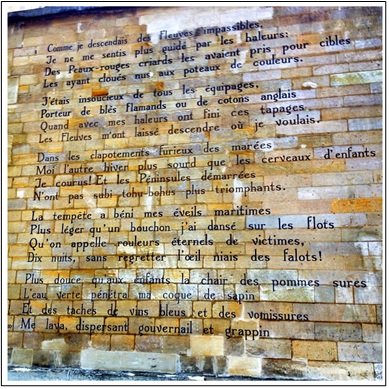

A street version of Le Bateau Ivre (Rue Ferou, Paris)Rimbaud had developed into a surly and foul-mouthed teenager, scandalising Charleville with his obscene language, unkempt appearance and provocative political and religious opinions. In the previous twelve months he had run-away from home several times. He had experienced brief periods of destitution, sleeping rough and scavenging for food. He had been arrested for travelling to Paris without a ticket and spent a few nights in jail.

Rimbaud had been invited to Paris to stay at the home of the poet Paul Verlaine. On the surface Rimbaud hoped that this introduction would allow him to conquer Parisian literary society and win accolades and acclaim for his poetry. However Rimbaud also had a much darker objective. He believed that to write truly great poetry he needed to become a seer, and this in turn required a long, prodigious, and rational disordering of all the senses, and that he must attempt to experience every form of love, of suffering, of madness. Opportunities for debauchery in Charleville had been strictly limited and Rimbaud intended to seek out all the opportunities that Paris had to offer. It is part of Rimbaud’s continuing appeal, that in the two years following his move to Paris, he not only lived the deranged and degenerate lifestyle his theory demanded, but also revolutionised his writing-style from a traditional form of French verse to the tumbling anarchic brilliance of his later prose-poems in works such as The Illuminations. That Rimbaud also managed to outrage the literary establishment with his infuriating and arrogant behaviour and with the outlandish originality of his poetry, only further enhances his legend; the visionary, the outcast, the prophet of revolt.

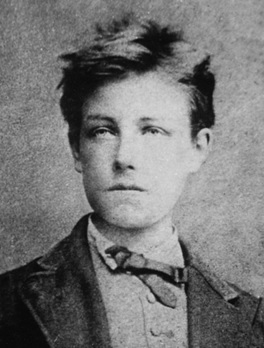

Photograph by Etiene Carjat - Rimbaud in Paris – Aged 17

1871 was a turbulent time, both for Rimbaud and for the Nation of France. Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III) had seized power in the coup d’état of 1852, founded the Second Empire and promptly declared himself Emperor. His rule had become increasingly unpopular in Paris and France was running into problems with its foreign policy and lack of allies. In 1870 Napoleon was manoeuvred into declaring war on Prussia.

The war went very badly for the French. On 1st September, after only six weeks of hostilities, Napoleon was captured at the battle of Sedan and most of the remaining French army was under siege. By 20th September Paris was surrounded and the government of the Second Empire had collapsed. Towards the end the year, Charleville and the surrounding area was bombarded and occupied by Prussian troops.

The new leaders of France founded the Third Republic and signed a humiliating armistice on 24th Feb 1871. The French had suffered over 100,000 dead and had been forced to concede territory. The new regime had little presence in Paris and was not widely accepted. In the resulting power vacuum and in a charged atmosphere of revolutionary fervour the Paris Commune was established by a combination of socialists and anarchists. The Commune lasted from 18th March to 28th May, when it was defeated by the National Government, resulting in a further great loss of life mainly on the communard side.

These events, in Rimbaud’s private life and in the life of the French Nation, form the backdrop to the Le Bateau Ivre. Ostensibly the poem deals with the escape and travels of drunken boat. The boat travels far and wide, sees many beautiful and terrible sights, before returning exhausted and disillusioned to its starting point.

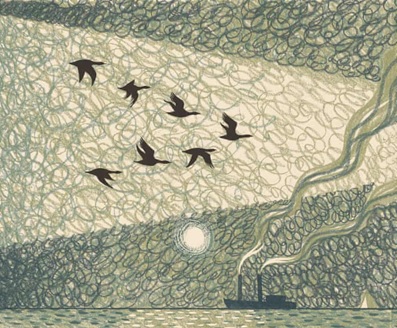

There have been many attempts to interpret this poem. Graham Robb in his biography of Rimbaud (Picador, 2000) describes some of these interpretations. They range from the view that the poem describes the heroic coming-of-age adventures of a young poet, to a love letter to Verlaine expressing his desire to be swept away on a tide of emotion, to a parable on the rise and fall of the Paris Commune. Robb himself argues that the poem only makes sense if Rimbaud is imagining the adventures of his absent father and hoping for his return. Nick Hayes in his marvellous illustrated version (The Drunken Sailor, Jonathan Cape, 2018) presents the poem as a detailed premonition of Rimbaud’s own life and death.

Illustration from The Drunken Sailor – for those setting out

Le Bateau Ivre is just as fresh and relevant today as it was in Rimbaud’s era. The prodigious power and beauty of the language and the psychological appeal and wide adaptability of the rise and fall allegory have not aged. Road movies, coming-of-age dramas and adventure stories continue to be popular genres as is the almost timeless search for meaning and truth. That there are a great many possible interpretations and semi-coherent messages buried deep within the poem only adds to our enjoyment. The poem is just as open and welcoming to our globalised twenty-first century minds as it was to Rimbaud’s small circle of friends one hundred and fifty years ago.

Just as there are many interpretations of Le Bateau Ivre there are also a great number of translations. The translated versions lose the sound and rhythm of the original and obscure the technical mastery of the poet. In French, the poem consists of twenty-five four-line verses with an ABAB rhyming scheme. Each line has the metrical form of an alexandrine. This tightly controlled formal structure is the almost diametrically opposed to the chaotic events and emotions the poet is describing.

There is a surprising amount of difference to be found in the various translations. Some translators have tried to preserve the literal meaning of each line and their translations give almost the same result as a translation programme. Other translators have been more concerned with preserving the poetic feel of the piece and have allowed themselves a far greater degree of freedom when translating particular words or phrases. In the many cases where Rimbaud uses a word or phrase in a surprising and original way it is not always clear how to proceed and some personal interpretation is necessary. This is difficult because we are far removed in time and space from Rimbaud’s world and our own personal prejudices or lack of knowledge can lead us into error.

Furthermore in the case of a translated poem, the translator lies between the poet and the reader and may be seeking to undermine the original intention of the poem. In writing this appreciation, the underlying assumption is that the poem is an allegory of a generalised youthful rebellion. The major consideration has been to preserve the beauty and balance of the poem especially when the poem is recited.

The poem is set largely in the past tense. The boat has returned from its travels and is recounting its adventures for our contemplation. In real life, Rimbaud is about to leave home and set out on his own grand adventure. That it all ends badly, both for the Boat and for Rimbaud, adds to the poignancy.

The poem begins slowly. The first two verses describe the poet setting off on his journey. He is angered by his lack of personal freedom and elects to kill off in his mind all the sources of authority that have until now plagued him. With his mother (the mouth of darkness), priests and conventional morality all banished, he is free to throw himself into his adventure and seek out every experience the world has to offer.

1.

As I was drifting down indifferent streams,

I no longer heeded the commands of my haulers,

Dark angels had taken them for targets,

And nailed them naked to glistening stakes.

2.

I no longer cared for my burdens,

Carrying Flemish wheat and English cotton,

And with my crew departed, the drudgery ceased,

The river let me travel where I pleased.

There are other accounts in literature that use the ship leaving port as metaphor. The Stone Roses in their song Tightrope use the words; The boats in the harbour / Slipped from their chains / Search for new horizons / Lets to the same; and James Joyce in his Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man finished with; And the black arms of tall ships that stand against the moon, their tale of distant nations. And the air is thick with their company as they call to me, their kinsman, making ready to go, shaking the wings of their exultant and terrible youth.

Verses three to six produce a sudden and gleeful acceleration followed by an incredible outpouring of joy at the newfound freedom. Some of the phrases here; Lighter than a cork I danced upon the waves / Sweeter than the flesh of sour apples to children / From that moment on I bathed in the Poem of the Sea, stand by themselves, irrespective of context, as fabulous images of fundamental beauty.

3.

Into the ferocious whip of winter’s tide,

More absorbed than a child, headlong I crashed!

Sea-cliffs wrenched from ancient rock,

Have not witnessed such a triumphant swagger.

4.

The storm embraced my seaborne passion,

Lighter than a cork I danced upon the waves,

Known to all as the eternal rollers of the vanquished,

Without once obeying the foolish eye of the lighthouse!

5.

Sweeter than the flesh of sour apples to children,

The green waters pierced my pinewood hull,

And rinsed away the stains of blue-wine and vomit,

Sweeping aside my rudder and my anchor.

6.

From that moment on I bathed in the Poem of the Sea,

Churned to milk, drenched in stars,

Devouring azure essences, where pale and unhinged,

A raving man might sometimes drown;

This is the ecstasy of the poet trumpeting his delight to the world and revelling in a new and unrestrained ocean of exciting phenomena. This is our first taste of freedom. We are like a fledgling taking to the wing for the first time, glorying in the flow of the air and whooping at the impossible vertigo of the land beneath us. The chutzpah of the poet is uncontainable. But as the initial waves of joy gradually subside the poet becomes aware of an unsettling undercurrent and his thoughts are slammed into the dark unexplored realm of desire.

7.

When suddenly out of the insane blueness,

Deliriums and lewd rhythms strike beneath the gleaming day.

Stronger than alcohol, louder than music,

Brew the bitter crimson waves of love!

This is the young poet, still only sixteen, embarking on his maiden voyage aboard The Drunken Boat, determined to fulfil his self-appointed role as a seer and experience every form love. Rimbaud’s tempestuous and much analysed relationship with Verlaine was still to lie in the future, and whatever was later to transpire between the two men, we imagine the young Rimbaud, shy and lacking in experience, full of trepidation and bravado, setting out from Charleville and plotting a course into the most delicate and treacherous of Parisian waters. Rimbaud was already, in metaphorical terms, attempting to be both the foolish virgin and the infernal bridegroom of his later poem.

At the Table by Henri Fantin-LatourDespite the strength of feeling, stronger than alcohol / louder than music, this is the only verse to explicitly mention love. The poet’s voyage is to be a voyage of self-discovery undertaken alone. The magnificent sights and sounds of the world described by the poet in verses eight to twelve can be read literally as travelogue, going where no one has gone before, or can be interpreted metaphorically as the development and transformation of the poet’s inner-being and a description of the intense emotional states has he experienced on his long and arduous attempt to become a seer.

Verlaine and Rimbaud are seated on the left

8.

I have come to know the skies split with lightning,

And the waterspouts, and the breakers and the cataracts.

I know the Night and the Dawn, and soaring like a flock of doves

I have sometimes seen the visions of shamans and sages!

9.

I have seen the drooping sun stained with mystic horrors,

Illuminating long violet coagulations,

Undulating like the performers in antique dramas,

The waves from afar unfurling their shimmering blinds!

10.

I have dreamed green nights of dazzling snow,

The kiss rising slowly to the eyes of the sea,

The circulation of inconceivable currents,

And the yellow-blue surge of phosphorus singing!

11.

For months on end I have followed the almighty swells,

Battering the reefs like herds of stampeding beasts,

Never dreaming that the luminous feet of the Marys,

Could muzzle by force these snorting Oceans!.

12.

I have struck, you must surely realise, incredible Horizons,

Where flowers mingle with the eyes of human panthers,

And rainbows stretch beneath the sea,

Like the pale bridles of glaucous herds!

Enid Starkie in her 1938 biography of Rimbaud describes a series of books, popular at the time of Rimbaud’s schooling, that may have been known to him and feature certain phrases related to those in the poem. One of these was La Mer (The Sea) by Jules Michelet. Michelet is today remembered as the first writer to use the phrase Renaissance to describe Europe’s break from the Middle Ages. His major work, Histoire de France, runs to nineteen volumes. La Mer was an illustrated semi-scientific summary of contemporary knowledge of the Sea, characterised by imaginative and poetic descriptions of such maritime phenomena as oceanic storms, creatures of the deep, and phosphorescence.

Illustration from La Mer by Jules Michelet (1861)In the English version of La Mer (translated by Mr W.H.D. Adams, Nelson & Sons, 1875, page 135) we find; transparent creatures which traverse the sea and the phosphorus - are actors in this serpentine comedy, which is close to Rimbaud’s choice of words in the ninth verse.

Rimbaud in verse eight - I have seen the skies split with lightning

Dr Starkie also explains the mysterious reference to the Marys in eleventh verse. The hooves of the cattle remind Rimbaud of the Camargue where the fighting bulls are bred. This in turn reminds him of the feast of The Three Marys celebrated in the town of Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer on the 25th May each year. The local legend is that the three Marys of the resurrection, along with their maid Sara-la-Kali (said by some to be Mary Magdalene’s daughter and now Patron Saint of the Gypsies), were exiled from The Holy Land and cast adrift in the Mediterranean. We imagine their small rudderless boat, buffeted by the wind and waves, running a little ahead of Rimbaud’s own drunken craft. As they wade ashore, their feet washed in the gentle warmth of the shallows, they symbolically conquer all the storms and savagery that the world has been able to throw at them.

There then follows an abrupt change of mood. Exploring, especially by oneself, is not just sweet embraces and pleasant scenery. The poet dwells on the absolute horror of some of the events he has witnessed and the disgust and shame he feels at the some of the things he has forced himself to endure. The predatory panthers of verse twelve were perhaps the first hint of the devastation to come.

13.

I have seen colossal swamps,

Where trapped in the seething reeds whole leviathans rot!

And amidst the silence, the crashing of oceans,

And distant panoramas collapsing into the abyss!

14.

Glaciers, silver suns, pearlescent waves, skies of red-hot coals!

Hideous wrecks lurk at the bottom of toxic gulfs,

And giant serpents, devoured by vermin,

Fall from twisted trees, reeking of dark odours!

Verse fifteen forms a brief pause in the horror as the poet reflects on some of the gentler things he has seen and is a rare moment of connection, feels that he would like to be able to share these experiences with children.

15

I should have liked to show to children, these dolphins

Of the blue, these golden shoals of singing fish.

Foams of flowers rocked my idle driftings,

And at times heavenly winds would lend me wings.

The poet is now lonely and vulnerable. The world is loud and invasive. He can hardly bring himself to continue. Mentally he is falling apart. He has lost interest in his discoveries. He longs for rest.

16.

Sometimes a martyr, weary of zones and poles,

The sea whose sobs sweetened my rollings,

Lifted its shadowy flowers towards me,

And I hung there like a kneeling woman.

17.

Almost an island, besieged on my shores by the brawls

And droppings of clamorous yellow-eyed gulls.

I voyaged on, whilst through my frayed cordage,

Drowned men sank backwards into sleep!

In verse eighteen the poet begins his summing up. The following four verses all swim into one another. The poet is lost mentally and physically. He is literally and metaphorically set upon by forces he can no longer contain or understand. He doubts that he can ever be saved. But amidst his confusion and his longing for quiet there are fragments of pride and defiance. He has bored through the reddening wall of the sky and swum with black sea-horses. He has written brilliant verse for those good poets who did not dare take the plunge. But now in all his desperation he longs for the security of home.

18.

But now, lost beneath the thicket of coves,

Hurled by the hurricane into the birdless ether;

I, whose wreck, dead-drunk and sodden with water,

Monitors nor Hanseatic vessels could have rescued;

19.

Liberated, smoking, and risen from violet fogs,

I, who bored through the reddening wall of the sky,

Spooned delicious jam to genteel poets,

Mixing lichens of sunlight with azure snot;

Just as the Punks of the 1970s wanted to smash up the corrupt and bloated music industry, with its cosy and conservative record companies and dinosaur rock bands, all conspiring to stifle new music and creativity, so Rimbaud, rejected by the conventional poets of his era, set out to expose their timidity with all the anarchy and vibrancy he could muster. In this analogy, Rimbaud was the ray of light shining through the corrupt oozing sludge.

20.

Who ran, speckled by pale electric moons,

A lunatic plank, with black sea-horse for company,

Where under July’s beating cudgel blows,

Ultramarine skies are crushed to burning funnels;

21.

I who trembled, sensing at fifty leagues,

The moans of rutting Behemoths, and heavy Maelstroms;

I, eternal spinner of the blue continuum,

Long for Europe with its age-old parapets!

The poet finishes his account with four quite different conclusions. Initially there is small spark of hope, the poet believes it may all have been worthwhile, but this soon turns to uncertainty and by verse twenty-three the poet just wants to curl up in a corner and die.

In verse twenty-four he remembers the sad and lonely world of his childhood and possibly leaves open a sliver of hope. Finally at the end of poem he arrives back at his starting point, and far from optimistically knowing the place for the first time (Little Gidding – TS Eliot) - past, present and future seem to collide in a vision of abject failure.

22.

I have seen archipelagos of stars! and islands,

Whose delirious skies call out to sailors;

- In these bottomless nights, do you sleep, are you banished,

O million golden birds, O Life Force of the future?

23.

But truly, I have wept too much! The Dawns are heart-breaking.

Every moon is atrocious and every sun diabolic;

Acid love has swollen me with toxic numbness.

O let my keel split! O let me sink to the bottom!

Verse twenty-four contains the single most poignant and affecting image in the poem. We can do nothing more than settle down beside the pond and gracefully arch our body into the shape of a silver swan and silently weep.

24.

If there is one water in Europe I want, it is the cold

Black pool where into the scented twilight,

A squatting child full of sadness,

Launches a boat as fragile as a butterfly in May.

In this image we find the whole of our existential angst. Separated from each other by the solidity of the world, and by the impenetrable barrier of our individual consciousness, and lacking the means to connect, we are like a forlorn child in need of affection and reassurance. Unable to communicate directly with one another, we are left stranded on a remote uninhabited island, with our only hope of rescue, a message floated away to distant lands, hidden in a tiny toy boat.

25.

Bathed in the bitterness of your languors O waves,

I can no more sail in the wake of carriers of cotton,

Nor enjoy the pride of flags and pennants,

Nor swim past the horrible eyes of the hulks.

The poet, disillusioned and weary, suspecting his adventures have been pure folly and believing his grandiose aims to have been nothing more than vanity, bathes in the bitterness of his defeat. He can no longer bear his life of adventure nor contemplate the stifling and restricting realities of provincial life. He recalls his earlier disgust at conventional bourgeois morality and rejects either a life of drudgery or one chasing the fickle baubles of literary fame and acclaim.

The impossible and impassable conundrum of what to do next is left unanswered. A gigantic boulder lies in our path and resists all our attempts to move it. The question of how to live our lives within a society which is manifestly unjust is the fundamental problem that must be solved anew by each successive generation in all lands and in all times.

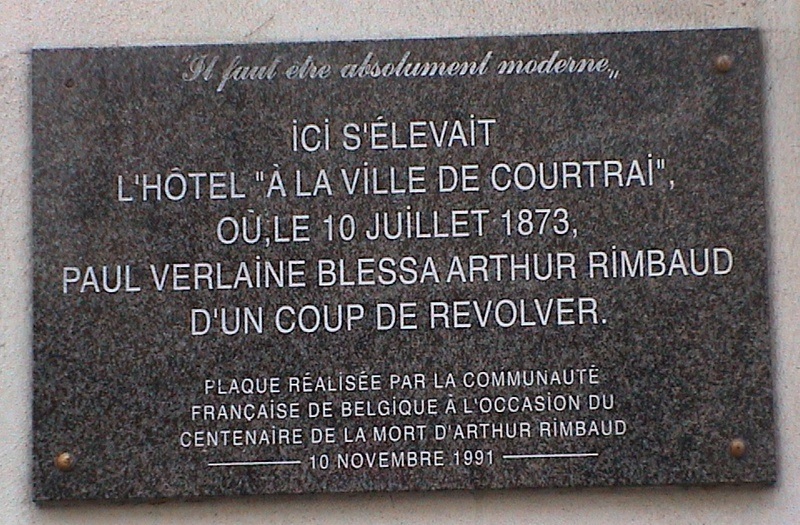

We know that Le Bateau Ivre was only a provisional conclusion. After leaving Charleville, Rimbaud spent the next couple of years on the road, travelling with Verlaine between London, Paris and Brussels. Rimbaud suffered endless poverty, addiction to absinthe and hashish, and the emotional torment of his affair with Verlaine. This all ended abruptly in July 1873 when a drunk and raving Verlaine shot Rimbaud in the wrist. Rimbaud returned to Charleville where he delivered his final magnificent and horrifying verdict in Une Saison en Enfer (A Season in Hell).

We also know that Rimbaud’s final answer was to abandon poetry completely. Rimbaud continued to travel widely but became much more conventional in his outlook, eventually settling down as a merchant in Ethiopia and attempting to trade his way to a fortune. But just as Rimbaud was free to reject poetry we are equally free to reject Rimbaud’s solution. Let us instead release our million golden birds to sing and glide across the globe, and through our openness and friendship, celebrate our magnificent and boundless freedom.

In different circumstances, Albert Camus, thinking of Sisyphus returning to the foot of the mountain, was to write; Every grain of this stone, every mineral glow of this mountain, full of night, forms a world. The struggle to reach the heights is enough to fill a person's heart. As it is with Sisyphus, so it must be with Rimbaud. He has succeeded in the long, prodigious and rational disordering of his senses, and has glimpsed into the unknown. I see again my skin ravaged with mud and pestilence, my hair and my armpits full of worms, and still bigger worms in my heart, writes Rimbaud in Adieu. He has experienced all things; the Dawns are truly heart-breaking, every moon is atrocious and every sun diabolic; and he has left the world with poems of indescribable beauty and scope.

Half a century later the writer Jean Genet was to declare; Oh let me be only utter beauty. This is the whole point. The utter and intense beauty of the lines leave us astonished and amazed. We are like a child standing in the light summer rain. Our eyes closed, our mouth open, tasting the delicious droplets as they splash and fizz on our tongue. These are our dolphins of the blue, our archipelago of stars, our green nights of dazzling snow.

I’ve walked on water, run through fire sang Joy Division, as the poet, in the intensity of his experience, and in the profundity of his suffering and in the vibrancy of his imagination takes us to the edge of the abyss and beyond. Maybe we have wept too much and maybe one hundred lines of verse cannot support the emotional weight we attach to them, but this gift, as fragile as a butterfly in May awaits us in the scented twilight beside a cold dark pool. Seek it out if you can.